TVR made its name for its hand-built sports cars that were as fast as they were fragile. Light, exceedingly powerful and utterly devoid of anything by way of a driver aid, TVRs were instantly identifiable from their aggressive aerodynamic bodies and the terrified, elated look on their drivers’ faces.

The exception to the rule in British car manufacturing, TVR was one of the first and greatest purveyors of the alluringly outlandish sports cars while the rest of the industry was busy making cars like the Morris Marina and Triumph T7; a touch of exotic in an otherwise conservative medium.

It's also got one of the most turbulent histories and reputations of any car manufacturer, with its gorgeous but notoriously unpredictable cars and with the company passing through several sets of hands and coming close to the brink of ruin on multiple occasions.

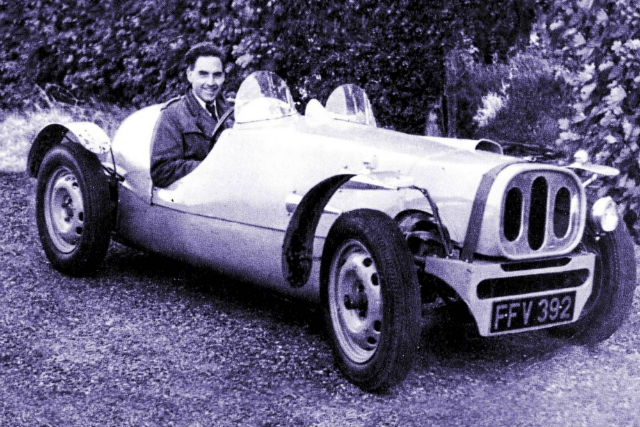

TVR’s amazing but slightly haphazard origins stretch back to the birth of its founder Trevor Wilkinson, an amateur in the truest sense of the word. Born in Blackpool in 1923, he left school with no qualifications before undertaking an apprenticeship as a mechanic and opening his own workshop, Trevcar Motors, in 1946.

To relieve the drudgery of performing oil changes, Wilkinson decided to build himself a sports car despite lacking any sort of formal engineering training whatsoever. His first successful creation was built on the remains of an old pre-war Alvis, and by 1949 he had built up enough confidence to create a car all of his own from scratch.

Humble but haphazard beginnings

Wilkinson’s car was entirely self-made using spare parts lifted from whatever he could find lying around: the wheels and back axle from a Morris, a Ford engine and suspension springs lifted from a local dodgem ride.

After a cousin bought the car for £325, Wilkinson renamed the company to TVR Engineering and would set himself up as something of an ad-hoc car builder, creating his own chassis for customers who could then specify different engines and custom bodywork.

A “production” TVR wouldn’t appear until 1954 when the TVR Sports Saloon debuted, complete with the engine from an Austin A40 and a plastic body. Slightly crude, perhaps, but even this earliest TVR was exciting, with three sold for £650 each – roughly £16,400 in today’s money.

Four years later TVR had moved into a bigger location, a former brickworks in Hoo Hill. By now, Wilkinson had developed another new chassis that featured independent suspension and its mechanicals packaged within a tubular steel spaceframe, allowing the seats to be set lower and the car to be closer to the ground to improve handling.

An order created for an American customer, who took the spaceframe and used it to create a racing car, inspired Wilkinson to finally start creating his own official cars, with the fibreglass Grantura unveiled at the New York Auto Show and ready for customer orders.

Short, stubby and squat, the Grantura looked a long way from later models like the Sagaris or the Tuscan, but already had a reputation for wicked handling and its wide choice of engines further broadened its appeal.

Orders started pouring in, but Wilkinson struggled to cope with the demand. Soon, TVR Engineering’s finances were taking a downward turn and the financiers who had been hired to keep the business afloat left the founder feeling so alienated from his own business that he left in 1962.

Interestingly, Wilkinson would actually continue to work alongside his former company for many years, taking sub-contract work for TVR after setting up an engineering business in his home town and continuing to develop his glass fibre car bodies.

Meanwhile, the Grantura had already given TVR a solid reputation for performance with the company rivalling Lotus as Britain’s best lightweight sports car builder. The basic ingredients of the car which Wilkinson had developed would form the basis of every TVR for the next decade or more.

Although Wilkinson’s departure threw TVR into a period of disarray, it trundled on and its first true success came with the Griffith 200, a car named after American car dealer Jack Griffith who had ordered a Grantura and fitted it with the same powerful V8 engine from the AC Cobra.

Initial turmoil and eventual success

Producing up to 267bhp but weighing less than 830kg, the Griffith 200 was able to smash its way from 0-60mph in just 3.9 seconds and on to a top speed of 150mph: an absolutely phenomenal time for the mid-1960s.

Essentially a factory-built hot rod, the Griffith 200’s immense power, light weight and short wheelbase made them notoriously difficult to handle, something which would come to define TVR cars in the next few decades, but which only fuelled the cars’ appeal and growing mythical status.

The year after the Griffith 200 was introduced, the company again changed hands with shareholder Martin Lilley taking the helm. Under Lilley’s stewardship, TVR became a little more polished with cars like the Tuscan V8 and the Vixen brought in to replace the aging Grantura.

TVR now sought to capitalise on its new-found successes and introduced the M Series chassis, which used the same body-on-frame construction as previous TVR models with a front mid-engine, rear-wheel drive layout.

Each car built on the M Series underpinnings, which included models like the 1600M, 3000S and Taimar, held a reputation for being extremely capable on the road, but usually at the expense of any comfort. Their high power outputs and low weight, coupled with bodies constructed of glass-reinforced plastic, meant they were as fast as they were loud.

By the late 70s Lilley felt that the marque had outgrown beyond the M Series and TVR brought in Lotus designer Oliver Winterbottom to design a sleek new coupe. Dubbed the Tamsin, its construction was fraught with difficulties after the US federal government impounded several TVR cars found not to meet emissions regulations, costing the company hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Even when it did finally make production, Lilley described the Tamsin as an “absolutely dreadful” disappointment, even though the car did receive relatively positive reviews despite its then-controversial wedge-shaped design.

The car’s disappointing sales figures coincided with the early 1980s recession in Britain, bringing TVR once again to the brink of financial implosion. Towards the tail end of 1981, Lilley transferred control of the company to wealthy businessman and TVR fan Peter Wheeler, who wasted no time in putting his stamp on the company.

Under Wheeler, the naturally aspirated and turbocharged V6 engines which had featured in a majority of the Lilley-era cars were gone, replaced with Rover V8s and displacements swole from 3.5-litres to 5.0-litres or more.

The Wheeler years

His first major development since buying out the company came with the introduction of the S Series models, which debuted at the 1986 British International Motor Show. Taking the same ingredients used on the M Series, the S Series marked the turning point in TVR’s flagging fortunes.

For a start, the company addressed one of its longest-running problems: the fact that it didn’t develop its own engines. In 1988 it sourced a V8 made by Holden for use in the S Series, but by the early 90s it set up its own in-house engine design unit, which created the Speed Eight engine, a 420bhp 4.5-litre V8 made of a special lightweight alloy.

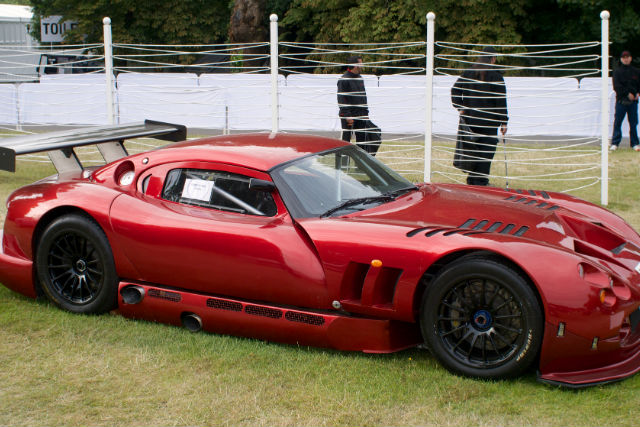

First appearing in the Cerbera and the Tuscan, the Speed Eight led to the development of the Speed Six, an inline-six version which was used in later versions of the Cerbera and Tuscan, as well as in cars like the legendary Sagaris and Typhon.

Able to produce more than 405bhp, the Speed Six still holds the record for the most powerful naturally aspirated inline-six engine ever fitted to a production car, and as if that wasn’t enough by 1997 TVR had the idea of bolting two Speed Sixes together to make the Speed Twelve V12.

Such an insane engine required a suitably insane car to be dropped into, and TVR unveiled the Project 7/12 concept at the 1996 Birmingham Motorshow, a car which dominated the show and attracted more onlookers than any other vehicle there.

Powered by a 7.72-litre version of the Speed Twelve, the Project 7/12 would be developed for production as the Cerbera Speed 12, a 1,000bhp hypercar that at the time aimed to be the fastest car in the world, toppling the then-champion, McLaren’s F1.

The racing version of the Speed Twelve engine developed a maximum of 675bhp, but for the road car TVR’s engineers could remove the regulation air restrictors. According to reports, the full fury of the Speed Twelve was enough to snap the central shaft of the dynamometer it was tested on, and the engine could produce more than 1,000bhp.

Unfortunately, the Cerbera Speed 12 would never make it to production. Once the prototype was built and tested on the roads, Wheeler himself decided that the car was too powerful and too dangerous for customers and so scrapped it at the eleventh hour.

In its time, TVR had endured mismanagement, misplaced ambition and global recession and come out the other end relatively unscathed, the early 2000s would see Trevor Wilkinson’s dream finally snuffed out.

Nikolay Smolensky, the son of a Russian oligarch, would purchase the company from Wheeler for a reported £15m in 2004 and despite falling sales he claimed he would turn TVR around and, crucially, also ensure it would remain a British company.

Downfall of TVR

However, over the next two years, production would plummet from 12 cars a week to just three and Smolensky laid off some 300 staff at the Blackpool plant. He later announced that production and final assembly would move to a factory in Turin, with only the engines still built in the UK.

Optimism remained intact nonetheless and TVR planned to release a range of new models, but even by the late 90s the price of a TVR car had started to approach £60,000 or more. Not bad, perhaps, for an entirely bespoke specialist sports car, but issues regarding reliability and quality started to see sales swiftly dwindle.

In order to comply with US emissions regulations, TVRs sold in the US had to be powered by the engine from a Chevrolet Corvette, something which didn’t sit well with fans and which would have cost them nearly £100,000 for the privilege of owning.

Smolensky split the brand into a number of different companies and eventually threw in the towel, turning his attention to building wind turbines under the TVR name. Production finally ceased in 2006 and there TVR lay dormant for nearly a decade.

In the interim period the TVR name faded into obscurity, but among the ashes rumours started to build. On 6th June 2013, it was reported that Smolensky had pawned off his entire ownership of TVR to two British entrepreneurs, Les Edgar and John Chasey.

Edgar and Chasey wasted little time and last year had already previewed the design of a new TVR car via sketches, with an aim to producing as many as four new TVR-badged vehicles by 2017, starting with the first as-yet unnamed sports coupe concept.

Designed by Gordon Murray, the man behind the legendary McLaren F1, the new TVR will be powered by a Cosworth-engineered version of the Ford Coyote V8 that powers the new Mustang and is due to arrive next year, priced from around £55,000.

That makes it a fair bit cheaper than any other TVR car in decades, but the car has all the performance to match its predecessors too, with the Cosworth engine reportedly producing so much torque that it fried the dynamometer TVR was using to test it – just as the Cerbera Speed 12 had.

Exact details are still few and far between, but the first new TVR in eleven years will be a front-engined, rear-wheel drive two-seater with a manual gearbox and it’s expected to adhere to the spaceframe/glass fibre recipe as its forebears.

First new TVR in eleven years

It’s proven exciting enough than every single one of the car’s first year production run of 250 models have already sold out, with customers putting down £5,000 deposits in order to secure a car before it’s even been publicly revealed.

Given TVR’s troubled history, there’s no guarantee that the resurrected brand will be a success, or indeed whether the new car will even make it to production. After all, the Sagaris 2 was in the pipework for years before having the plug pulled on it.

But the company’s new helmsman Edgar has stressed that he’s fully committed to a “well-funded, well-supported organisation” with a “vastly experienced management system”, lightyears away from the patchy operation TVR’s previous owner operated.

Of course, until the new car is unveiled and finally unleashed you’ll just have to take TVR’s word for that. Still, the initial signs are positive and if TVR has proven anything, it’s that it’s more than capable of weathering virtually any storm thrown at it. In Edgar’s own words: “We’re here to stay”

Copy from: https://www.carkeys.co.uk/news/the-turbulent-history-of-tvr-britain-s-wildest-carmaker

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário